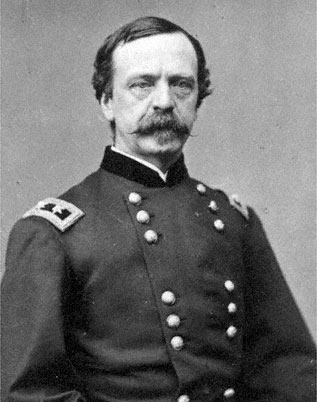

3.) Dan Sickles– Anyone who knows me knows that I am not a big fan of Dan Sickles. Why’s that you ask? Sickles was an example of a type of general which plagued both sides of the Civil War: he was a political general. Dan Sickles was an infamous general, brash and well connected.

Dan Sickles was a product of Tammany Hall, the political machine of New York City. Working his way up the political ladder, being elected to the New York State Assembly in 1847. He would serve under President Franklin Pierce in London, England, in 1853, and upon his return to New York he would be elected to the New York State Senate (1856), where he would serve until 1861.

Sickles gained pre-war fame in 1859 when he killed Phillip Barton Key II, the son of Francis Scott Key (author of the Star-Spangled Banner) in cold blood in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House. Sickles did so because Key was apparently having an affair with his wife (though Sickles had caused an uproar only a couple of years earlier by bringing a known escort to England with him instead of his pregnant wife). Sickles went to trial, and became the first person to plead Temporary Insanity and win. Almost like shooting a man in the middle of 5th Avenue and getting away with murder, eh?

Sickles had well connected friends in Washington, D.C. In 1861, he would actually raise his own brigade of volunteer infantry: that’s four whole regiments. Most people who were well connected and raised their own companies or even regiments. With some help from his friends, Sickles would retain command of his volunteers in 1862 after having to petition Congress to allow him to continue to command his brigade. Sickles would rejoin his brigade, the famous “Excelsior Brigade”, in time for McClellan’s battles around Richmond. The Excelsior Brigade was made up of four regiments: the 70th New York, 72nd New York, 73rd New York (also known as the 2nd Fire Zouaves, mostly made up of New York City Firefighters) and the 74th New York. With the Excelsior Brigade, he fought at the Battle of Seven Pines outside of Richmond, as well as in the notorious Seven Days Battles, in which he also proved himself to be competent. Sickles was not in command of his brigade during the Second Battle of Bull Run, and his men missed the engagements at Antietam as well as at Fredericksburg.

Following the Battle of Fredericksburg, Sickles was promoted to Major General and was given command of the III Corps. Sickles fought at Chancellorsville, where his disdain for West Point educated generals grew. On May 2nd, he pushed to assault the Confederates, who he thought were retreating. In reality, they were Jackson’s Corps moving into position for their surprise flank assault, known to history as Jackson’s Flank Attack. If Sickles had been allowed to attack, the Battle of Chancellorsville may have had a totally different outcome. The next day he again pushed back and questioned the timid Hooker when Hooker gave orders to move out of a position on the field known as Hazel Grove. The terrain was ideal for a defensive stand, something that Sickles pointed out. However, Hooker overruled him, and when Sickles pulled back, the Confederates occupied the position and proceeded to hammer the Federal positions with artillery fire. Sickles III Corps suffered heavy casualties from this, and he did not forget it.

Sickles did not end up as Number 3 on my list for abusing his men. Like Hooker and McClellan before him on this list, Sickles was adored by his men. That was because Sickles took care of them. Sickles is on this list because of his actions at Gettysburg.

On July 2nd, 1863, Sickles was tasked with protecting the Union Left Flank. This covered the left end of Cemetery Ridge, as well as Little Round Top and Big Round Top. Upon his arrival on the field, Sickles took a look at the ground. In some parts of the line, specifically the lower slope of Cemetery Ridge before climbing back up Little Round Top, Sickles noticed ground that was higher than what he was on. This ground would be the Peach Orchard and Devil’s Den. Without orders (and against them when they were delivered), Sickles moved his corps forward, off of Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge, and into positions in the Peach Orchard, along the Emmitsburg Road, and Devil’s Den. What Sickles was thinking was of Hazel Grove at Chancellorsville only 2 months (not even) earlier. He could see in his mind’s eye the Confederates putting artillery on those rises over looking part of his position and pouring artillery fire on his men, slaughtering them. However, what he did not consider was the negatives of such a move.

The first problem was he created a salient in the defensive line. A salient is a bulge, meaning that his forces went from having one side exposed to the enemy (their front) they had three sides exposed to them. This meant that the enemy could hit them on any side, which could result in things like enfilade fire (being fired on from multiple interlocking areas) or even being completed surrounded and cut off from reinforcements. Moving that far forward would make it harder to get reinforcements and resupply from the rest of the army. Not something you want to have happen.

The second problem was that this left the Union Left Flank exposed. For those of you who have been to Gettysburg and have stood atop Little Round Top, you’ll know what I’m talking about. If you haven’t been there (yet), I’ll do my best to paint the picture for you. When you stand up on Little Round Top, you have an amazing and unprecedented view of the battlefield. Pre-20th Century commanders were not always able to have a bird’s eye view of their battlefield, or see the entire battlefield from above. Looking west from Little Round Top, you could see Warfield and Seminary Ridges, the ridges which the Confederates would launch their attacks on July 2nd and July 3rd. Turn slowly to the north, and you can see Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, Rose Woods, the Wheatfield, the Triangular Field, the Slaughter Pen, the Codori Farm and the site of Pickett’s Charge, and eventually you can look straight down the Union Battle line, the famous Fish Hook. In the distance you could see Culp’s Hill, and when you start to look east, you see the interior defensive lines and the supplies of the Union Army. Meade wanted the hill occupied by the army, specifically by Sickles. With artillery on Little Round Top, no Confederate would be safe approaching Cemetery Ridge. However, Sickles only left the Signal Corps on top. If the Confederates could take the hill and move around the flank, it could be disastrous for the Union Army.

Meade rode out personally to order Sickles to move his men back to Cemetery Ridge. Sickles argued with him, and as they did so, the Confederates launched their attack on the Left Flank. It was too late for Sickles to move the III Corps back. Confederate Divisions (the way the Army of Northern Virginia was structured, one division was the same size as a Federal Corps) hit Sickles’ salient: the division of Lafayette McLaws being the division to strike the biggest blow. The III Corps was shattered as a result, but credit must be given to the men who fought here: they fought tooth and nail, inflicting heavy casualties on the Confederates. Here regiments like the 73rd New York Volunteer Infantry, made up of Firefighters from New York City, held their ground grudgingly against the oncoming Confederates. Their numbers were whittled down, and they were forced to give way. The III Corps on July 2nd went into the battle with 11,924 men at the morning muster; 4,210 men would not be there at the end of the day. The attack destroyed the III Corps, and the battle was almost lost here.

Dan Sickles moved his headquarters to the Trostle Farm, and he tried to coordinate and regroup his Corps here. However, they were being pushed on three sides by the Confederates. It was at the Trostle Farm, while on horseback, that he was wounded. A cannonball tore through his right leg, mangling it. He was removed from the battlefield on a stretcher, a cigar clamped between his teeth. It was one last attempt at bravado for his men, to boost their morale. His leg would be removed, and he had it sent to the Army Medical Museum, where it still resides today. After the war, he would visit his amputated leg.

Following the battle is where Sickles really earned his spot on the list. He was removed from military duty due to his wound, but he was back on the battlefield he knew all about: Capitol Hill and Washington, D.C. Sickles immediately began to attack the character of General Meade, saying that Meade didn’t win the battle, but that he, Major General Daniel E. Sickles, won the battle by moving the III Corps into the Peach Orchard. Being the Spin Doctor that he was, Sickles said that if he didn’t move the III Corps out to the Peach Orchard and “stall” the Confederates for as long as he did, then the Confederates would have crushed his position (still), crashed through the Union lines, and the Union would have lost the battles. Congress actually agreed, to a certain extent, and even awarded Sickles the Medal of Honor for his service at the battle.

Sickles was not an all around horrible guy; granted, he would face embezzlement charges later in life, but Sickles was fundamental in writing and passing legislation that would form the Gettysburg National Military Park. This also includes his efforts to buy up private land on the battlefield and to erect monuments. Funny enough, the man who thought so much of himself is one of the only major commanders who fought in the battle to not have a statue or monument of himself or dedicated to him. The only one that comes close is a marker standing on the site of the Trostle Farm where he was severely wounded. When asked why there was no memorial to him, Sickles supposedly said, “The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles.”

Sickles is Number 3 on the list because his actions specifically on July 2nd, 1863, put the entire Battle of Gettysburg in jeopardy. This is considered to some historians as being the closest the Union was to losing the Battle of Gettysburg. At one point, because of this mistake, the Confederate army had no organized military force between them and Cemetery Ridge. He failed to take into account the full scope of the terrain he occupied, as well as the orders given to him by General Meade, and therefore failed his objective at Gettysburg and makes it to Number 3 on the list.