When Myths Fade Away

How long does it take for myths to be revealed as just that: myths? Stories we tell ourselves when we don’t know (or don’t want to admit) what the truth really is? Some myths are harder to kill than others.

On September 8th, 2021, one of the largest statues of Robert E. Lee was finally removed. The iconic statue had been erected on Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, in 1890. It would be the first of many other Confederate Statues erected on the avenue, including a statue to famed Confederate Cavalier J.E.B. Stuart. Needless to say, the removal of the statue has created quite a stir as it normally does when Confederate monuments are discussed in the mainstream. But the conversation of whether the statue should have been removed is not one I want to have today. It is one I have talked about, I feel, ad nauseum, and I do not believe I can offer any newer insights today than I did however long ago I wrote about monument removals.

No, what piqued my interest is the comments made by former President Donald Trump. I want to throw out a disclaimer: I do not intend to discuss his policies, or to discuss him as a person. That is not the intended direction I want to take. When the statue of Robert E. Lee was removed, President Trump made a formal statement denouncing the state of Virginia (and specifically Governor Northam) and praising the legacy of Robert E. Lee. Now, this is obviously not the first time President Trump has displayed his love for the former Confederate General and loser of the American Civil War. His statements of support go back to the Charlottesville Confrontation in 2017 over the removal of Lee’s statue there. But the statements Trump made on the 8th are, well, interesting.

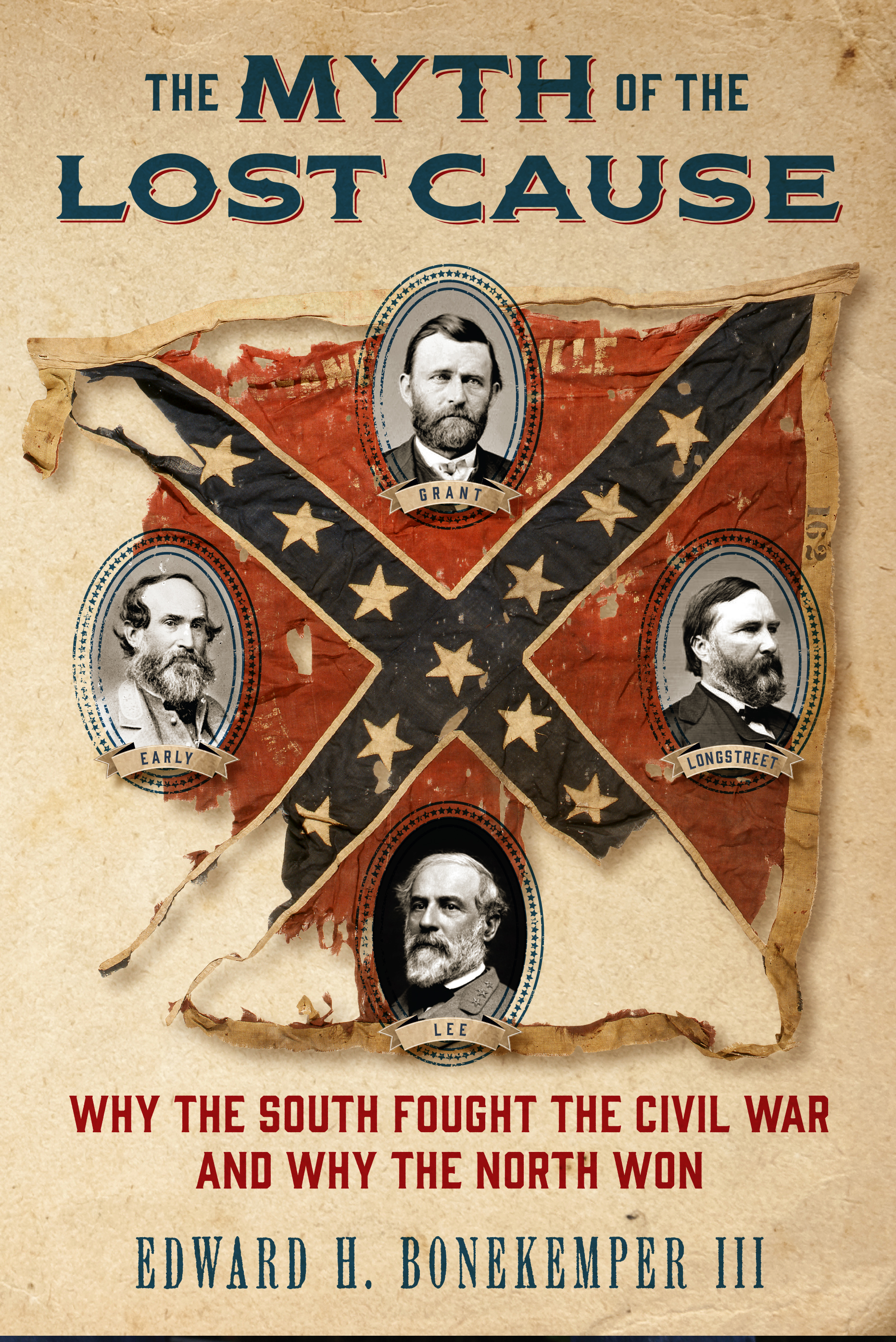

There are statements which, in a way, are kind of true. “Robert E. Lee is considered by many Generals to be the greatest strategist of them all.” There are indeed many generals, and there have been many generals, who have revered Robert E. Lee as a great strategist. Dwight D. Eisenhower had a picture of Robert E. Lee in his office. Winston Churchill had heaped praise on Robert E. Lee, saying “Lee was the noblest American who had ever lived and one of the greatest commanders known to the annals of war”. Lee has always been held in high regard, and in large part this is because of that phenomenon I’ve talked about called “The Myth of the Lost Cause”. The statement, however, is incorrect about Robert E. Lee being the “greatest strategist of them all”. While some generals believe he was, Robert E. Lee’s track record in the war would prove otherwise.

Here’s a statement chock full of false: “Robert E. Lee chose the other side because of his love for Virginia, and except for Gettysburg, would have won the war”. Gettysburg is most widely known as the “High Watermark of the Confederacy”. In fact, if you visit the battlefield today there is a marker which is labeled as the High Watermark of the Confederacy (though there is debate about the accuracy of this. Some argue that the marker shows the furthest point through Union Lines that Virginia troops advanced to, but that North Carolinians farther along the wall by the Abraham Brian Farm advanced deeper behind Union lines. Others argue that the Mississippians of William Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade made it even farther behind Union lines the day before, and both are upset over “Virginian Bias”. Sheesh. Like that’s a thing.)

The thing about the American Civil War is that, like most modern wars, one battle doesn’t always determine the outcome of the entire war. Keep in mind, the Battle of Gettysburg was fought on July 1st-3rd, 1863; Robert E. Lee did not surrender the Army of Northern Virginia until April 9th, 1865, and the last Confederate forces did not surrender until the summer of 1865. And Gettysburg wasn’t Lee’s only defeat, as the former President makes it seem. Prior to Gettysburg, Lee’s first combat command was in West Virginia in 1861. He was defeated in the Battle of Cheat Mountain, fought from September 12-15th, 1861. Cheat Mountain is located in eastern West Virginia, in the counties of Randolph and Pocahontas. Ironically, he was defeated by General George B. McClellan. Lee would fight McClellan again throughout the late spring and early summer of 1862 during the Seven Day’s Battles, and just over a year after their initial confrontation at Cheat Mountain they would clash around Sharpsburg, Maryland, in the Battle of Antietam on September 19th, 1862.

Lee’s loss at Cheat Mountain would have the same characteristics of his other lost battles, with the biggest one being the lack of coordination and control over his subordinates. This is something that Lee would never be able to fully reconcile and would cost him the war.

Even after Gettysburg, what some people would consider victories for Lee really weren’t victories at all. At the Battle of Mine Run in November 1863 it was Meade’s hesitation to launch a Fredericksburg Part Deux that gave Lee a “victory”. The Overland Campaign of May-June 1864 would end up with Lee technically “winning” a series of battles (the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Yellow Tavern, North Anna River, Totopotomoy Creek, Trevilian Station, and Cold Harbor) but here is where Lee does not show his prowess as the “greatest strategist of them all”.

Robert E. Lee was not a “big picture” general. By this, I mean that he had a hard time looking past Virginia and at the greater view of the war. But if you scale that down to the Overland Campaign, I will hazard a guess as to say that Lee expected to beat the Army of the Potomac in a battle, and the Army of the Potomac would simply retreat to winter quarters or closer to the Potomac. And why wouldn’t he think that? That was what every single Union General he faced did after losing a battle. Heck, Meade did that just as recently as November 1863 during the Mine Run campaign. But Grant and Meade did not do that in May of 1864. In fact, they simply marched around Lee. Grant’s objective was to do battle with Lee and to wear the Army of Northern Virginia down. Did he want to seize the Wilderness? Was Spotsylvania Courthouse a strategic goal? How about controlling the North Anna or Cold Harbor? Winning those battles would be a bonus. But Grant wasn’t simply looking for military targets to seize. Not until he got to Petersburg, anyway. He wanted to wear the Army of Northern Virginia down, because he knew that was what needed to happen in order to win. Lee got the “victories” during the Overland Campaign, but those victories led to his overall defeat. In a way, it is very similar to what happened to Hannibal Barca’s army during the Second Punic War against the Romans.

Following Hannibal’s stunning (and still mystifying) victory at the battle of Cannae on August 2nd, 216 BC, Hannibal’s Carthaginian Army was considered unstoppable. Ever since crossing the Alps, Hannibal owned the Romans at every battle, and Cannae was his Deus Ex Machina. One of Hannibal’s goals was to get Rome’s allies on the Italian peninsula to abandon her and to join Hannibal. He thought that if he could do that, not only would his army be larger, but he could surround Rome and embarrass Rome the way Rome embarrassed Carthage following the First Punic War. However, there was a fatal flaw in Hannibal’s plan. As he won, the Romans stopped coming out to engage him. Instead, the Romans would go to city-states in Italy that had switched sides to the Carthaginians, and they would besiege them. Hannibal would be forced to respond to their aid, and by the time he arrived the Romans would be gone and would besiege another city. Hannibal was forced to put out fires until his army was finally recalled to Carthage in 203 BC.

What was the point of that little sidebar? The point is that while winning the single battle was great, it negatively impacted the outcome of the war. In this case, each one of these victories cost Lee thousands of soldiers, soldiers that he could not replace.

Now let’s say that Lee did win at the Battle of Gettysburg. What the former President forgets, as do many other people, is that things were not going good for the Confederacy in July 1863. See, while Lee was invading the north, Grant was busy besieging the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. On July 4th, 1863, the day after the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, General John Pemberton surrendered his Army of Mississippi to Ulysses S. Grant. Note that this was not only not the first Confederate army to surrender to Grant, and it would not be the last.

Vicksburg, Mississippi was the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. It was the only thing keeping the United States from splitting the Confederacy in half. If Lee won at Gettysburg, Vicksburg still would have fallen.

Also on July 3rd, 1863, the Union Army of the Ohio commanded by William S. Rosecrans seized the city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Chattanooga was a vital rail hub for the Confederacy, sending much needed supplies and reinforcements from the western Confederacy to the eastern Confederacy. With Chattanooga and Vicksburg severed, a victory for Lee at Gettysburg would have been, at the time, shrunken in comparison. Yay, Lee won in Pennsylvania. But in the process the rest of the Confederacy is collapsing, and the Union Army is continuing to close in on him.

I have always felt that Gettysburg was more of a must win for the Union than it was for the Confederacy, because the Union needed to know that it could decisively defeat the Army of Northern Virginia in the Eastern Theater. It seemed to be the only theater of the war where the Confederacy had somewhat competent commanders in charge compared to their counterparts in Georgia and Mississippi.

“If only we had Robert E. Lee to command our troops in Afghanistan, that disaster would have ended in a complete and total victory many years ago.” Okay, this is the last one. But can we begin with the fact the Robert E. Lee surrendered his army? Lee did not win the actual fighting of the American Civil War (though his legacy and memory has done just fine). Also take into account that Lee had a higher casualty rate than his opponents. On average, his army suffered 20% casualties during major campaigns. In comparison, Grant’s armies in four separate theaters suffered 15% casualties. This is due to Lee being overly aggressive and being aggressive when he did not need to be aggressive. During his time as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee had a habit of launching massive attacks when he did not need to launch them. As a result, thousands of lives were lost when they did not have to be in the first place. Does anyone think a war in Afghanistan directed by Robert E. Lee would be any different? I don’t think so. And here is my biggest reason why: unlike Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee did not learn from his mistakes.

July 1st, 1862: the outskirts of Richmond, Virginia. It is the seventh day of the Seven Day’s Battles. The Union Army under George B. McClellan is making their way to the James River. McClellan has psyched himself out over the past six plus days, and he is beginning his withdrawal back up the James River to Harrison’s Landing. On Malvern Hill he places Col. Henry J. Hunt, his Chief of Artillery, in charge of fortifying the hill. Hunt proceeds to place 171 artillery pieces on top of Malvern Hill, in a position where if the Confederates wanted to attack and take the hill, they would have to march straight into the Union guns. That should be enough of a deterrent, right? Not for Lee. Lee launched an assault on Malvern Hill. His attack was viciously and decisively repelled. Out of 30,000 Confederates engaged on Malvern Hill, the Confederates suffered 5,650 casualties. D.H. Hill, a division commander within the Army of Northern Virginia, estimated that half of the casualties suffered during that day were from artillery shells. A year and two days later, on July 3rd, 1863, Lee would launch the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge under similar circumstances. He assaulted an enemy who outnumbered him, had a defended position along a ridgeline, and had to assault over open ground where every Union battery could train their sights on his advancing soldiers and tear them apart.

The point is, either because he was incapable or he did not want to, Lee did not learn from his mistakes. This is a criticism I have long held of the general, and it is something that his Union counterpart, Ulysses S. Grant, did well. When Grant had a setback, he learned from that mistake and grew stronger. His performance at Shiloh is a great example. Robert E. Lee would continue to launch unnecessary assaults throughout the war, long after Gettysburg, and even when it was more prudent to stay on the defensive. Take a General like this now and place him in command of an army that is tasked with A.) Hunting down a specific Terrorist and B.) fighting a counterinsurgency. In my opinion (and I want to reiterate this is my opinion), I would rather have Ulysses S. Grant in charge of the war in Afghanistan and not Lee. Lee would not lead the US to victory; if anything, Lee would lead us into a deeper disaster.

Myths are created for a reason. They are established to help explain things that are unexplainable. However, the myths outgrow their usefulness when those unexplainable things are explained. I feel that we are at a point where we should be able to agree that the legacy of Robert E. Lee that we were not only taught, but that so many believe, is just a myth. We know the truth. We know the casualty reports. We know the shortcomings and failures militarily. We know that he was not that good of a general, as well as not being a super stellar American or human being. Maybe with the removal of this monument and the former President’s whimpering about Lee being a great American, we are finally seeing this myth begin to be dispelled.